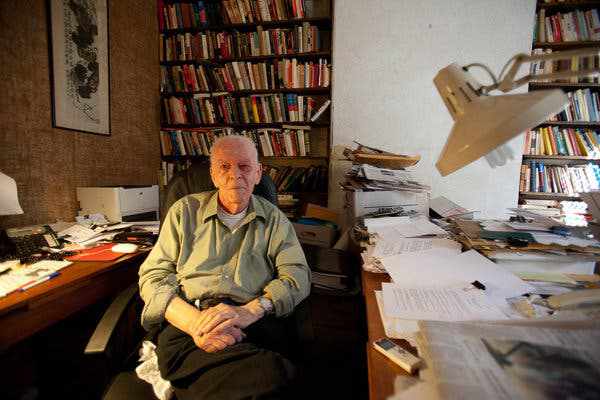

Gene Sharp is one of the most singular people I have had the privilege to meet. His study, with books lining the walls and teetering precariously in piles on every available surface, emphasised his scholarly side. The tributes to him from activists around the world who had been inspired by his work highlighted the revolutionary in him. When he died in 2018, the New York Times said, “What Sun Tzu and Clausewitz were to war, Sharp was to nonviolent struggle — strategist, philosopher, guru.”

Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela are valorised globally for their teachings on non-violence and their leadership of the movements that advanced freedom in their countries. Each has a global or national day dedicated to celebrating their accomplishments and values. Each has multiple awards, streets and institutions named in their honour. There are statues of them in plazas around the world. Their faces are featured on postage stamps and currency notes.

Gene Sharp, on the other hand, lived, worked and died in relative obscurity. Yet his work has been just as consequential in inspiring and informing movements for democracy from Myanmar to the Colour revolutions, and the people’s uprisings of the Arab Spring.

Speaking of his academic legacy, Mary Elizabeth King says, “He studied Gandhi longer and more ruthlessly than anyone in my ken, although he thought that Gandhi should be fathomed as complex, contradictory, paradoxical, and possessed of human frailty.” “To Gene,” she says, “idealizing Gandhi as mahatma (“great soul” — homage that made Gandhi uncomfortable) endangered the perception of his insights. He fully grasped Gandhi’s striking understanding of temporal power, articulated while Gandhi was still in his thirties in South Africa.” “In this,” she emphasises, “he discerned a subtlety in Gandhi’s thought: the elemental choice is not violence versus nonviolence, but action as opposed to inaction.” As Tina Rosenberg summarises, “Nonviolent action is not an appeal to a dictator’s conscience. It is a war, but fought without arms.” And, “Research studies support this point. As a way to topple dictators, nonviolent struggle has double the success rate of violent resistance. And the bigger the role played by mass nonviolent resistance, the freer the country and the more durable the freedom that emerge.”

This distinction is vital even today, as movements for equity in the USA and South Africa find themselves having to contest the sanctification and sanitisation of their leaders, as others seek to turn their teaching into apolitical, inspirational quotes, even deploying them in the service of ends deeply antithetical to these leaders’ values.

Gene Sharp spent his entire life working single-mindedly on deepening his understanding of the principles and practice of non-violence. If Gandhi provided the inspirational manifesto, Gene Sharp wrote the practitioner’s manual. His list of 198 methods for non-violent action has served as a toolkit (before that word became popular in India as an excuse for prosecuting young activists) for campaigners on the ground facing ruthless dictators, though he refused to take credit for their successes. When I mentioned to him that activists in Egypt claimed that they had been trained by Serbian activists from OTPOR!, who had been guided by Gene’s writing, he said that was unlikely since his works, as far as he knew, had never been translated into Arabic.

His modesty was rivalled only by his pragmatism. His arguments for non-violence rely on the cold calculus of effectiveness rather than on moral authority. To some, this dilutes them. To many others, it makes them blueprints for action.

On the 93rd anniversary of his birth, with sabres rattling again from the Ukraine to Taiwan and Ladakh, we may all do well to brush up our reading of Gene Sharp’s writings.

Write a comment ...